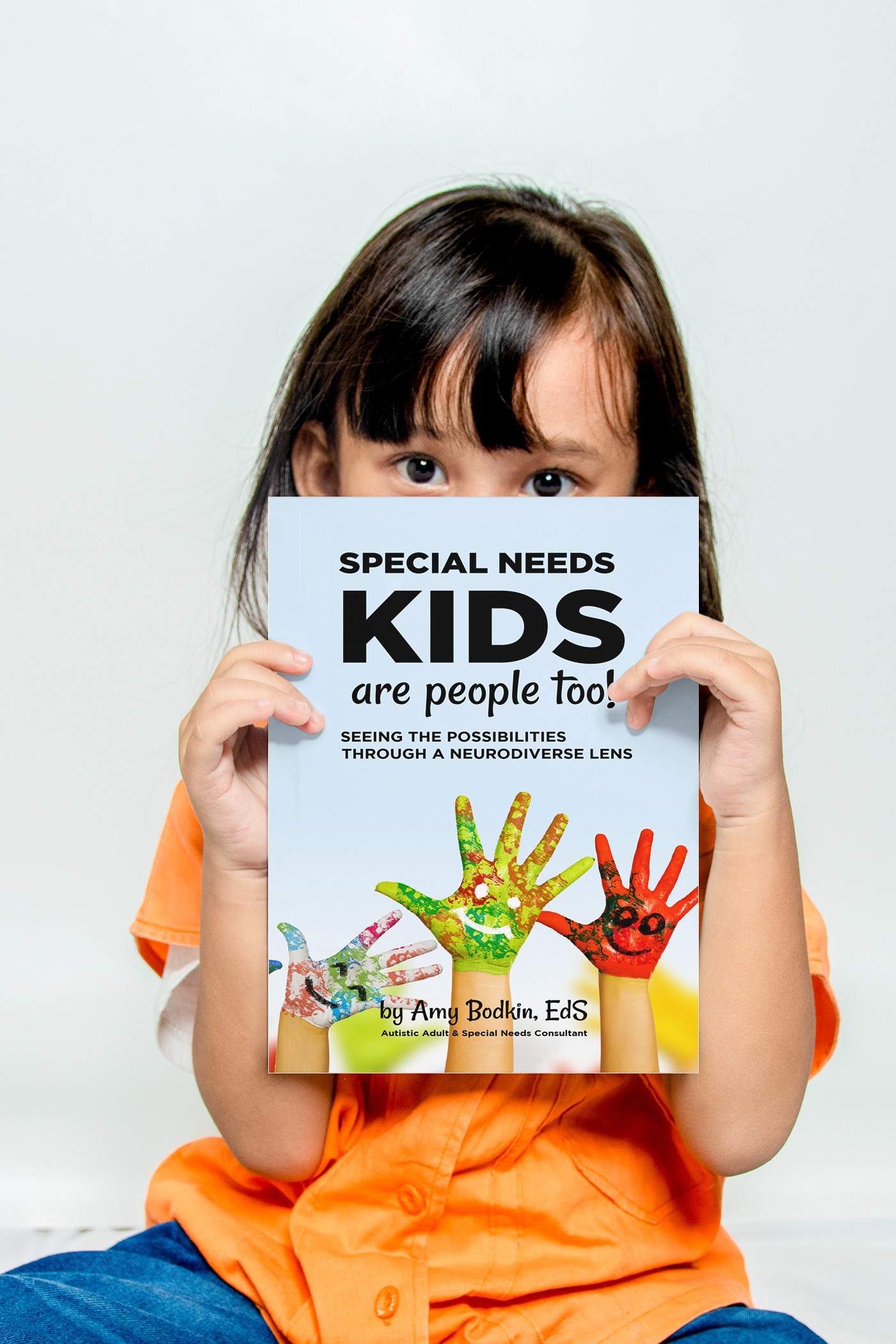

Order your copy of Amy’s book today!

SPECIAL NEEDS KIDS ARE PEOPLE TOO

Seeing the Possibilities through a Neurodiverse Lens

by Amy Bodkin, EdS

It’s a book you don’t want to miss!

As an Autistic adult and school psychologist with an emphasis in neuropsychology, Amy Bodkin has had the opportunity to support children with a wide range of needs and diagnoses: in public schools, private practice, private schools, and home schools worldwide. Her motivation has always been to make the world a more friendly and truly accepting place for children like herself.

But how do we do this? Society has been working at increasing awareness and acceptance for a while, and yet children are still falling through the cracks. But pushing for awareness and acceptance isn’t enough. We need a road map forward. And that road map must, at its foundation, include seeing and appreciating each child as an individual. Can we combine that with what we currently know from the research about pediatric brain development? Yes!

Special Needs Kids Are People Too: Seeing the Possibilities Through a Neurodiverse Lens seeks to chart just such a path forward and takes you to the intersection of child development, neuropsychology, and education, making these dense subjects more accessible for parents and practitioners alike.

This remarkable book provides a road map for parents and practitioners attempting to help children labeled with:

- Autism

- ADHD

- Learning Disabilities

- Sensory Processing Disorder

- Genetic conditions

And children who experience or have experienced:

- Anxiety

- Trauma

- Stress

- Serious Health Conditions

In this book, you will find:

- Strategies for seeing each child as an individual, not just a diagnosis, and how this can positively impact growth and development.

- Insight into the neurodiverse perspective and how it can help you rethink your approach to education.

- Tips for advocating for children with special needs and encouraging others to see their potential.

- Expert guidance on navigating the challenges and celebrating the strengths of children with special needs.

- The unique expertise of Autistic adult Amy Bodkin, who holds an Educational Specialist degree with an emphasis in Neuropsychology, a Master’s degree in Educational Psychology, and works as a Consultant for both families and professionals.

Brilliantly blending personal experience with decades of wisdom from the fields of child development, neuropsychology, and education, Special Needs Kids Are People Too is an invaluable contribution to the discussion of what acceptance truly looks like.

This timely and important book shows parents and practitioners the innumerable ways in which they can help children truly thrive.

Praise for Special Needs Kids Are People Too!

“Amy’s book is a big hug for the families who are in the trenches of trying to understand their unique children.”

– Katelyn Rodriguez, M.S, CCC-SLP, Speech Pathologist

“Amy Bodkin’s philosophy of seeing each child as an individual rather than a diagnosis is refreshing and emphasizes the inherent value of every child. The book beautifully balances theory with practical applications, offering guidance on creating supportive environments that celebrate neurodiversity. Her approach of fostering balance and confidence in children is both compassionate and practical, making this a must-read for anyone involved in the education or care of children with special needs.”

“Amy Bodkin’s philosophy of seeing each child as an individual rather than a diagnosis is refreshing and emphasizes the inherent value of every child. The book beautifully balances theory with practical applications, offering guidance on creating supportive environments that celebrate neurodiversity. Her approach of fostering balance and confidence in children is both compassionate and practical, making this a must-read for anyone involved in the education or care of children with special needs.”

– Amber O’Neal Johnston, author of A Place to Belong: Celebrating Diversity and Kinship in the Home and Beyond

“Invaluable for anyone seeking to understand and support neurodiverse individuals better.”

– E.G. Brown, PhD, Licensed Marriage and Family Therapist

“As a school psychologist and a parent, I have read many books on autism or other special needs, behavior, and parenting. Amy Bodkin’s perspective is unlike any of the others in that she integrates her educational training, her personal experiences as an autistic adult, and her approaches to parenting and homeschooling neurodiverse children into an organized guidebook for anyone who lives or works with children with special needs. She outlines her consultation style in a manner that will help parents to actually understand their own child from a new perspective, and to celebrate their child’s individual differences.”

– Laura Neal, EdS, School Psychologist

EXCERPT FROM:

SPECIAL NEEDS KIDS ARE PEOPLE TOO: Seeing the Possibilities Through a Neurodiverse Lens

by Amy Bodkin, EdS

CHAPTER 2: WHY SPECIAL NEEDS?

“Part of the problem with the word ‘disabilities’ is that it immediately suggests an inability to see or hear or walk or do other things that many of us take for granted. But what of people who can’t feel? Or talk about their feelings? Or manage their feelings in constructive ways? What of people who aren’t able to form close and strong relationships? And people who cannot find fulfillment in their lives, or those who have lost hope, who live in disappointment and bitterness and find in life no joy, no love? These, it seems to me, are the real disabilities.”

– Fred Rogers

Since I started using the term “special needs” for my work, I have taken a lot of flak for it from fellow Autistics, professionals, and parents. People often ask questions like, “Why don’t you use neurodivergent?” or “Why don’t you use exceptional?” And I have honestly given this a lot of thought because if I am going to run counter to what everyone is telling me, then I need to have a good reason and know why I disagree with everyone else!

So, why not use neurodivergent? I use it all the time to describe myself, so why not use it in my work? The reason is that I work with families who do not always fit neatly into the description of neurodivergence.

The definition for neurodivergence, according to The Oxford Dictionary, is “divergence in mental or neurological function from what is considered typical or normal.”

But this definition doesn’t always fit children with a physical disability or a severe medical condition, a parent with an autoimmune disease, adopted children, foster children, or one of the many other situations requiring special care. Of course, some of these situations may lead to a difference in neurology, but that doesn’t mean those individuals are ready to self-identify as neurodivergent. Sometimes they have to mourn the loss of their own previously held expectations of who they were and how the future might look. Sometimes they just have to recognize and acknowledge their legitimate feelings before they are ready to take on a new moniker and, indeed, a new identity!

Then why not use exceptional? It sounds so positive! We get the opportunity to highlight how everyone has things that make them excellent!

The definition of exceptional according to The Oxford Dictionary is “unusually good or very unusual.” But in educational settings, the term exceptional has been, more times than not, used to describe children who are identified as gifted. This brings up a completely different set of word problems.

In the United States, giftedness is an educational identification based on a student’s Intelligence Quotient (IQ). Most people’s experience with IQ scores is that they measure one’s intelligence, which would make sense. Except, that is not correct.

In the late 19th century and early 20th century, psychologists explored the concept of intelligence and endeavored to develop a method for measuring people’s intelligence. Eventually, they were able to develop a test that they thought could gauge intelligence, what we now know as a standard IQ test. The belief was so strong that the United States military used these tests on a mass scale during World War I to determine which enlistees should be selected as officers. Of course, that led to a large amount of data that could then be used for further research on intelligence. This also led to the unfortunate and inaccurate conclusion by researchers that certain ethnic groups were more intelligent than others.1 This, of course, was not true but was a bias in the test.

This further led to the United States Supreme Court upholding the right of the government to force sterilization on citizens with low IQ scores (Buck v. Bell, 1927).2 This, then, resulted in a more significant percentage of people of color being forcibly sterilized than their white counterparts. While eugenics has somewhat fallen out of favor, the Supreme Court’s decision has never been overturned.

We have learned from intelligence testing over the last century that despite our most audacious dreams, IQ tests do not actually measure intelligence. Like the people of old endeavoring to build a tower to the heavens, we also thought ourselves equal to the Divine. And, like them, we, too, have been humbled. This doesn’t mean that intelligence tests are entirely useless. They can offer valuable insights into how a person processes information at a particular moment; however, they cannot, and never have been able to, predict future ability.

As you can see, intelligence tests have been used to separate people into those who are “valuable” and those who are not. They have also been used to divide students between those deserving of an enriching curriculum and those pulled from all elective subjects for remedial assistance in reading and math. And the reality is that there is no basis for such decisions.

I once had a teacher in high school who told my class that one year she had been given her class roster, and each student had a number next to their name. As she looked at the numbers, she concluded that they must be her students’ IQ scores and that she had better do an outstanding job teaching this year to live up to her students’ potential. She later found out that those numbers were their locker numbers, but it taught her a valuable lesson about the power of our perceptions.

It’s important to note that gifted students also face unique challenges due to their atypical development. But we have a tendency to minimize the challenges of gifted students and only focus on their strengths. Likewise we also have a tendency to minimize the gifts of students with learning disabilities and tend to focus solely on their challenges. It is ignorant to label giftedness positively and learning disabilities negatively. Both identifications represent imbalances in development, and each comes with its own set of strengths to celebrate and weaknesses to support.

A similar effort to categorize has been happening to Autistics as well as within the Autistic community. Until recently, children considered “higher functioning” were diagnosed with Asperger’s Syndrome, while children considered “lower functioning” were diagnosed as Autistic. Even though the Asperger’s diagnosis no longer exists, many people still choose to identify themselves as having Asperger’s. Why is that? Some people prefer to stick with Asperger’s because it was the diagnosis they were given. But, sometimes, people stick with Asperger’s to separate themselves from “lower functioning” Autistics. And there can be reasons to do this as it can affect how others, especially those in authority, may judge you.

However, some opt to identify as Autistic to unite their voices and advocate for the greater good of the Autistic community. Others choose to identify as Autistic due to the complicated legacy of Hans Asperger, the man for whom Asperger’s is named.

The first time anyone discussed Autism was in the late 1930s when Hans Asperger spoke to Nazi officials about the unique abilities of some of his Autistic patients, though they were not yet called Autistic. Was he acting as a willing agent of the Nazis by doing their dirty work deciding which children had value to the state and which did not and should be sent to the first death camps? Or was he working as an undercover operative doing what he could to preserve lives? The world may never know for sure, as the motivations of a man’s heart go with him to the grave. What we do know is that the complicated history of Autism, including Hans Asperger himself, continues to have an impact on the words we choose today. You can learn more about this fascinating history in the book Neurotribes: The Legacy of Autism and the Future of Neurodiversity by Steve Silberman.

The words we use matter. So why not use the term exceptional? As you can see from the examples of intelligence testing and Asperger’s, exceptionalities have been used to separate people into those who have real value and those who don’t. That does not inspire a sense of equality or brotherhood. However, recognizing that we all have struggles, weaknesses, and needs unites us as we realize what we have in common as human beings. We all struggle in some way, at some point, because that is how growth happens, and that is what it means to be a living being, to constantly be in a state of growth and change. In fact, only when we stop growing and changing do we go from living to dying.

The challenges we all experience vary significantly from person to person, and it almost always diverges from the nonexistent “golden average”. So why not change the term from “special needs” to “human needs?”

The Oxford Dictionary defines special as “not ordinary or usual; different from what is normal.”

In truth, many of these needs are special in that they are outside the norm and not naturally accommodated for, while other needs are more common and thus naturally accommodated for.

In an ideal world, all needs would be taken into account as “human needs” without this emphasis on a diagnosis proving their necessity. In fact, many accommodations work equally well, if not better, for people without a diagnosis. However, in our less-than-perfect world, I suspect that, in some ways, a drive toward “human needs” would eventually denigrate the real struggles of very real, though not typical, needs that are not being accommodated.

Trying to emphasize that these are all just “human needs” could also allow us to identify our needs in a way that says, “I’m not different. I’m just like everybody else.” And why would it be a problem to see no difference? We are, after all, members of the same human race. But it is a problem. We have learned over recent decades that being color-blind to racial differences does not lead to true inclusivity. In fact, it does quite the opposite and bars us from celebrating what is truly beautiful and valuable about our differences, shaped by our unique journeys.

There is an episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation (yes, I’m a Trekkie!) in which the Genome colony risks annihilation because their carefully engineered society cannot easily be separated from their planet. It turns out that the solution was found in a piece of technology worn by Geordi, the Chief Engineer of the Starship Enterprise, a blind man. The VISOR (Visual Instrument and Sensory Organ Replacement) he wore provided him with a sense of sight. But he never would have been born in the Genome colony because his existence was not valued. And yet, it was his very existence and the technology created to support his need that protected the Genome colony from extinction.

We have talked about the importance of challenges in human growth and development, and this importance is more than just skin deep. Our very bones must experience just the right amount of stress to grow correctly, and we must all experience stress in some form or another to continue our existence. Stress is a necessary aspect of life that knows no difference in class, religion, race, or diagnosis. And, when we are willing to identify with each other, to say, “Yes, I am different like you are also different,” we realize that we all have special needs. We come to realize that we all have needs that must be acknowledged and accommodated at some point in our lives. Perhaps we are not as different from others as we may have originally thought. Seeing ourselves in others, despite apparent differences, humanizes us by acknowledging our diverse needs.

Humans, by nature, are driven to rank and categorize our world to make sense of the confusion we see around us. We tend to lift some people on a pedestal so high that we cannot reach them, while we trample others beneath our feet, relegating them to the muck and mire of human refuse. Neither of these extremes leads to relationships that bring true belonging and acceptance, and changing the words we use will only change the outward dressings.

To see genuine acceptance and true belonging, we must invest instead in eye-to-eye relationships. These are the only kind of relationships that can allow people to meet on equal, if albeit different, footing.

ORDER YOUR COPY TODAY! >>> PURCHASE ON AMAZON HERE!

I look forward to helping you see the possibilities.

REFUND POLICY

All sales are final on digital products.

Katie Griner –

I’ve read (or tried to read) several books that offer help with parenting kids with special needs. Never have I read a book like this one. I read it all in two short sittings. Amy is uniquely qualified, and it is unlike any book I’ve read before. She understands what it is like to be a parent to special needs kids. A lot of books are written by “experts” or teachers, who have gained knowledge by research and observations, but this book reads more like a friend, who knows what it is like to be there, and she also has the professional training and experience to be of help. She is also autistic, so she can understand better what a kid is processing/feeling than an outside researcher or teacher (or even a parent sometimes). This book basically outlines her philosophy on education, why she feels the way she does, and how she puts this into practice in her own life and consulting professionally. I love that she looks at each child as a whole, making sure there are no physical or emotional health issues that are being overlooked – most specialists just try to take care of the symptoms that they are qualified to address. She will look at the whole picture and then offer suggestions on other specialists you might benefit from seeing. And the case studies at the end – they really offer a great visual of the unique and caring way in which she helps kids. She truly cares about each kid (and each parent). Reading this book really kinda changed my view on education and life. I’m looking forward to implementing some of the suggestions from this book in my own home. [Advanced Review Copy]

Amanda Owens –

This book is a deep dive into Amy’s clinical philosophy written in a personable tone that feels worthy to be called the foundation for a dissertation but with humor, personal stories, and related asides about a myriad of interesting topics. The reader doesn’t have to have a background or special interest in philosophy, education, or mythology to understand the well outlined introduction to several schools of thought that have influenced the author deeply (per her own frequent admission!) and the varied case studies may be particularly engaging for parents that have worked with Amy, will work with Amy, or simply want to understand some of the thought processes that go behind the scene when a psychologist consults with the whole child in view. For reading this book, an enjoyment of deep discussions is beneficial, a basic understanding of Star Trek a bonus, and a love for the wellbeing of every child a must. You may learn something, but you’ll probably learn a lot of things.

Rosie Rossi –

A quick read with a wealth of information! As a psychologist, autistic adult, and parent of an autistic children, Amy provides valuable insight from both professional personal viewpoints. The book is divided into two parts- underlying philosophy and practical application. I love how the philosophical underpinnings pull from various sources but the underlying message is one cultivates a strength-based and compassionate mindset towards special needs children. The practical application portion takes those views and provides a holistic outline for addressing learning concerns. A ‘bottom-up’ approach is applied- ensuring a child’s physical and emotional needs are met first and foremost, which is essential for learning! Highly recommend this book for professionals working with neurodivergent children or parents hoping to better understand their neurodivergent child.

E. G. Brown, PhD, Licensed Marriage and Family Therapist –

As a licensed marriage and family therapist I have had the opportunity to read and review numerous books on neurodiversity. However, Amy Bodkin’s “Special Needs Kids Are People Too! Seeing the Possibilities through a Neurodiverse Lens” stands out for its unique perspective and holistic approach.

The author, Amy Bodkin, is not only a school psychologist but she is an autistic adult and the parent to two autistic children. This first-hand experience lends authenticity and depth to her insights. Her personal journey through the neurodiverse world provides a rich tapestry of experiences that she weaves into her narrative, making it relatable and engaging.

Bodkin encourages readers to view the child holistically, attending to their physical, emotional, and mental states. At the heart of her philosophy and approach is the belief that you take your cue from the child. That is, if we take careful notice of what our children are saying and doing, we are better attuned to their needs. By encouraging us to see the whole child, she fosters empathy and understanding, crucial elements in supporting neurodiverse individuals.

The book draws from various fields, including psychology, religion, philosophy, and education, to argue that autistic children share the same needs, desires, and longings as everyone else. This interdisciplinary approach enriches the narrative and broadens the reader’s understanding of how neurodiverse individuals see the world. Bodkin references renowned theorists like Charlotte Mason, Jean Piaget, and Abraham Maslow to describe how children learn. These references provide a theoretical framework that supports her arguments and enhances the book’s academic credibility.

As a reader, I found myself learning more about navigating a neurodiverse world and gaining insights into how neurodivergent adults and children perceive their surroundings. This knowledge is invaluable for anyone seeking to understand and support neurodiverse individuals better. Finally, this book serves as a helpful review for professionals in child and human development. It offers a fresh perspective and practical strategies that can be incorporated into therapeutic practices. It also serves as a reminder of the importance of empathy and understanding in our work.

Amber O’Neal Johnston –

Amy Bodkin’s philosophy of seeing each child as an individual rather than a diagnosis is refreshing and emphasizes the inherent value of every child. The book beautifully balances theory with practical applications, offering guidance on creating supportive environments that celebrate neurodiversity. Her approach of fostering balance and confidence in children is both compassionate and practical, making this a must-read for anyone involved in the education or care of children with special needs.

Laura Neal, EdS, School Psychologist –

As a School Psychologist and a parent, I have read many books on autism or other special needs, behavior, and parenting. Amy Bodkin’s perspective is unlike any of the others in that she integrates her educational training, her personal experiences as an autistic adult, and her approaches to parenting and homeschooling neurodiverse children into an organized guidebook for anyone who lives or works with children with special needs.

She outlines her consultation style in a manner that will help parents to actually understand their own child from a new perspective, and to celebrate their child’s individual differences. This is a refreshing contrast to society’s tendency to focus on “fixing” a symptom or behavior rather than focusing on the underlying reason for it and starting from there.

Reading how the web of philosophical underpinnings intertwined in her mind and experiences to form such clear and concise theories of her own was fascinating from the neurotypical reader’s perspective.

The case studies bring practical sense to professionals and parents, in understanding the whole child and incorporating into practice or parenting some of the methods that have made her such a successful consultant and autistic parent of autistic children.

Her perspective is a compassionate rope of knowledge and experience, yet with a foundation based on love, grace, respect, and balance – a refreshing reminder to any reader overwhelmed by society’s perspectives on treatments and education.

Katelyn Rodriguez, M.S, CCC-SLP, Speech Pathologist (verified owner) –

As a neuro-affirming Speech-language Pathologist and family educator, I am constantly on the lookout for resources to recommend to families and other professionals. Amy’s book is the perfect mix of research and anecdotal evidence that creates, in effect, a big hug for the families who are in the trenches of trying to understand their unique children. As a late-diagnosed individual myself, I couldn’t help but think about how different my experience would have been growing up, if my parents and teachers had had access to a book such as this. Amy presents a relatable and digestible narrative of what it means to be neurodivergent in a world that is made for the neurotypical. Using her experiences as a neurodivergent professional and parent, Amy introduces many thought provoking topics related to wellbeing of the whole child, rather than focusing on fixing what others consider “deficits” or “problems.” This refreshing approach is a must-read for parents and educators, no matter where you are on your neuro-affirming journey.

Lynne Moore –

This was a very interesting book and reading it was like having a conversation with a friend about everything from different educational theories to Star Trek. There is so much good information about topics such as Charlotte Mason and Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. There is no assumption of previous knowledge on these topics and they are explained very simply. Amy is very good at making connections between an idea that might seem complicated and relating them to something like Star Wars which helps to make things very understandable. She even discusses health and autoimmune issues and made connections I found very helpful. I love how Amy sees each child as their own person!

Lucas –

This book will not be for everyone. If you need a book that cuts straight to concrete strategies, you’ll have to look elsewhere. But its target audience, particularly neurodivergent Wikisurfers like me, will find a lot to spark the imagination. I have read many parenting books and still a lot of the information was new and fascinating to me, nicely tied together with the author’s personal and professional expertise. If you are someone who really likes to know “why” rather than just “what” or “how,” I think this book has a lot to offer.

Katie M –

In Amy’s book, Special Needs Kids Are People Too, she blends her own experiences as an autistic person while highlighting the challenges of how our systems fail neurodiverse children. It is an honor to have the chance to hear her perspective. The way Amy is able to connect these personal experiences to the system at large is a great feat, and she does so in an effortless way. The language she uses makes it easy to digest the excellent points she makes regarding stigma and lived experience of those who function differently than what is considered “typical.” This is a book for parents who have children with special needs, those who identify as neurodivergent themselves, and anyone else who is looking to educate themselves from a first-hand account of what it is like to live in a world that is set up for neurotypical people. I have also had the opportunity to work with Amy professionally, and she always has such a beautiful way of interacting with parents who expressed concerns for their child with special needs. She helped the families I worked with immensely, and her book is a reflection of all the great work she does for others.

Kimberly Bennett, LPC –

I am deep into reading Amy’s book and cannot put it down! Amy takes us on a journey with lessons in history, biology, psychology, philosophy, and faith. She challenges us to go deeper – to examine all we have learned and all we thought we knew while also inviting us to learn more and see the world and ourselves through new eyes. Part teacher, part guide, and part fellow traveler, her book invites readers to hold a mirror up to society and themselves. Introspection, while challenging at best and painful at worst, is necessary for awareness, understanding, and growth. Amy endears readers to look beyond labels to see the child as a person. As a fellow clinician and a homeschooling mom of a child with learning differences, I have a love/hate relationship with labels. While labels are necessary for common communication, they are terms and nothing more. They are not the sum of a person. Identity is so much more. Kimberly Bennett, LPC – Founder/CEO http://www.homeschoolcounselingnetwork.com

Dr. Janice Cohn (verified owner) –

I’m a psychotherapist who has often worked with “quirky” kids who are creative, artistically talented and exceptionally clever. They are not “typical” and often can be awkward in school and in social situations.

Whether they are on the autistic spectrum, or not, Amy Bodkin’s passionate, well written book will be of great help to the parents of the young people I see in my practice. Actually, I think it should be read by all parents, educators and mental health professionals because of her breadth of knowledge, insight and practical advice. We need more Amy Bodkins to compassionately and astutely translate for adults the challenges and triumphs of special needs kids.

Julie Ross –

As a Charlotte Mason homeschooling expert, I can with certainty that this is the book that has been missing from the conversation of Miss Mason’s first educational principle “children are born persons.”

Bodkin’s insights into the neurodiverse perspective are eye-opening. She challenges readers to rethink traditional approaches to education and child development, encouraging us to appreciate the unique strengths and challenges of neurodiverse children. Her tips for advocating for children with special needs are incredibly empowering, helping us to see and nurture the potential in every child.

What I loved most about this book is its emphasis on seeing each child as an individual, not just a diagnosis. Bodkin’s strategies for fostering growth and development are practical and easy to implement, and they truly make a difference. The book covers a wide range of conditions, including Autism, ADHD, Learning Disabilities, Sensory Processing Disorder, and genetic conditions, as well as issues like anxiety, trauma, stress, and serious health conditions.

The expert guidance in this book is unparalleled. Drawing on her professional expertise and personal experiences, Bodkin offers practical advice for navigating the complexities of supporting children with special needs. Her dual perspective enriches the content, making it both compelling and informative.

Overall, Special Needs Kids Are People Too is a must-read for any parent, educator, or practitioner involved with children who have special needs. It’s a compassionate and insightful guide that provides practical tools and a fresh perspective on neurodiversity. Amy Bodkin’s compassionate approach will inspire and empower you to make a meaningful difference in the lives of children with special needs. The world has needed an educational philosophy of special needs, and this book so richly provides it.

Julie Ross, CEO A Gentle Feast

Alicia Cichon –

Wow! So much history and well researched philosophy included in these pages! Amy Bodkin’s philosophical approach to parenting is well thought out and laid out here, with such interesting bits of history sprinkled throughout.

I’m glad I purchased and read this book when I did, as I was simultaneously making my way through another book that examines adult disease as it pertains to childhood unmet needs. This reminder of Maslow’s hierarchy, and the most important needs of every human and every child, is so important in creating a learning and living environment that feels safe. How can my children thrive, even with the best educational planning and intent, if other more important needs aren’t properly met?

I’m also a Charlotte Mason home educator and huge fan of her work and philosophy. I feel that Charlotte Mason was brilliant and has to have been led by the Holy Spirit in producing her method of education.

Amy Bodkin, likewise has been blessed with a gift – one which allows her to see patterns everywhere – including in putting together the puzzle that can be a child’s physical health along with their unique learning difficulties. Where Charlotte Mason lacked in giving tools for educating neurodiverse children, Amy comes in and shapes the CM method for all, and comes alongside other parents in the trenches.